Submission to the Standing Committee on Appropriations: Parliament of South Africa on the 2020 Appropriations Bill

- Published:

[et_pb_section admin_label="section"] [et_pb_row admin_label="row"] [et_pb_column type="4_4"][et_pb_text admin_label="Text"]

Submission to the Standing Committee on Appropriations: Parliament of South Africa on the 2020 Appropriations Bill

Submission to Standing Committee on Appropriations

Attention: Mr Darrin Arends

Committee Secretary

Email: daarends@parliament.gov.za

Tel. (021) 403-8105 / 071 363 2273

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This submission was compiled by SAFCEI (Southern African Faith Communities’ Environment Institute); a multi-faith organisation committed to supporting faith leaders and their communities in Southern Africa to increase awareness, understanding and action on eco-justice, sustainable living and climate change.

This submission focuses primarily on an analysis of energy sector appropriations. Key concerns raised include how Eskom has become a major drain on the fiscus. The extent of bailouts required by Eskom at the same time as tariff increases is having a negative impact on citizens. As a major public entity, Eskom is meant to be financially independent of the fiscus, but sustained state capture, inflated contracts and a failure to do maintenance have resulted in a crisis at the public utility. Unresolved issues of state capture and corruption at Eskom persist. Poor supply chain management and contracting practices remain an issue. Repeated bailouts to Eskom are resulting in money that could have been spent on education, health or other areas of spending being diverted. Increasing tariffs are raising the cost of living and the cost of doing business. It is therefore a matter of urgency that the corporate governance and financial management at Eskom and in other departments and entities in the energy sector is brought under control.

A second focus of the submission was to analyse the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economy and on the energy sector. Reduced economic activities due to the Covid-19 pandemic have an implication for the demand for electricity. Previous demand modelling no longer holds true. Even post contagion, the demand for electricity is unlikely to return to previous levels, due to business activities having been lost. There is decreased fiscal space for large capital projects and yet at this time, and despite the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) not envisioning new nuclear before 2030, but rather at a pace and scale that is affordable, the Minister of Energy wants to push ahead with a plant life extension at Koeberg, 2500MW new nuclear and with South Africa’s commitments to the Grand Inga imported hydroelectricity project. Simultaneously, operational wind farms are being told that they would periodically be required to curtail their supply to the grid during the national lockdown in line with the force majeure (act of God) clause in their contracts.

The public interest must be put first. Constitutional provisions for public participation and transparency must be upheld. Prior to any procurement, there would need to be a Section 34 Electricity Regulation Act determination in place with public participation.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- We call on Parliament to exercise its Constitutional oversight mandate rigorously in respect of proposed capital projects in the energy sector.

- We call on Parliament to ensure that the Department of Energy and Eskom make transparent what financing mechanisms they intend to use for the proposed 2500MW new nuclear build.

- We call on Parliament to ensure that Eskom is more transparent about making loan agreements and contracts publicly available.

-

When Treasury sets requirements that public entities must meet when they receive bail outs or obtain loan guarantees, compliance with these requirements should be monitored as part of Parliament’s oversight role. Officials in public entities not meeting the requirements should be called before committees to account for their failure to comply.

-

The shareholder compacts for all public entities should be made available in the public domain for scrutiny.

- Appropriations and Finance Committees to request full costings for infrastructure projects. These costings must include provisions for decommissioning of plants and management of radioactive waste.

- SAFCEI calls on government to abandon nuclear energy entirely. South Africa does not need nuclear in its energy mix. It is a costly and unsafe power generation option.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

ESKOM AS AN INCREASING DRAIN ON PUBLIC FINANCES

THE FINANCIAL LINK BETWEEN HOUSEHOLDS, BUSINESSES, MUNICIPALITIES AND ESKOM

ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON SOUTH AFRICA

IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON DEMAND FOR ELECTRICITY

COVID-19 AND A JUST ENERGY TRANSITION

SOUTH AFRICA’S INTEGRATED RESOURCE PLAN

THE ROLE OF NUCLEAR IN SOUTH AFRICA’S ENERGY MIX

CONCLUSION

ABOUT SOUTHERN AFRICAN FAITH COMMUNITIES ENVIRONMENT INSTITUTE

SAFCEI (Southern African Faith Communities’ Environment Institute) is a multi-faith organisation committed to supporting faith leaders and their communities in Southern Africa to increase awareness, understanding and action on eco-justice, sustainable living and climate change.

It was launched in 2005 after a multi-faith environment conference which called for the establishment of a faith-based environment initiative. We have a broad spectrum of membership, including African Traditional Healers, Baha’i, Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, Jewish, Quaker, and a wide range of Christian denominations.

We emphasise the spiritual and moral imperative to care for the Earth and the community of all life. We call for ethical leadership from all in power and speak out on issues of eco-justice, encouraging citizen action.

INTRODUCTION

The 2020 Appropriation Bill was tabled in February 2020 at a time when Covid-19 had begun to impact other countries, but was not yet impacting South Africa. In response to the call for submissions on the Appropriations Bill, Safcei has taken the impacts of the pandemic that are already apparent into account.

The novel Coronavirus outbreak is having a profound global impact. Many countries have opted for lockdown as a way to manage the influx of cases that are placing a massive burden on public health facilities. The need to 'flatten the curve' to spread the demand for health services over a longer period of time has an obvious economic impact. This has profound implications for national economies and for global trade. A global recession that is deeper and more lengthy than the 2008 recession seems likely. South Africa had entered into a technical recession prior to the Covid-19 pandemic impacting and economic activity has been severely buffeted since lockdown was instituted.

Reduced economic activities have an implication for the demand for electricity. Previous demand modelling no longer holds true. Even post contagion, the demand for electricity is unlikely to return to previous levels, due to business activities having been lost. At this juncture in which South Africa’s economy is profoundly impacted and demand for energy is down, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy has announced its intentions to procure 2500MW of new nuclear power by 2024.

On 07 May 2020, Minister Mantashe indicated to the Portfolio Committee on Mineral Resources and Energy that government will be looking at small modular reactors and the procurement process will get underway with the issuing of a Request for Information. DMRE has outlined that the project will be undertaken on a build, operate and transfer basis, insisting that there will be no immediate requirement of funding from the state .

At the same time, DMRE has indicated that it will embark on a 20-year extension of Koeberg Nuclear Power Plant’s life to be completed by 2024 - the year in which Koeberg was due to be decommissioned. DMRE also intends to procure a new Multi-Purpose Reactor and a Centralised Interim Radioactive Waste Storage Facility by 2024. Plans to proceed with South Africa’s participation in the Grand Inga project to obtain imported hydropower from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are also still on the table despite the project being fraught with massive challenges which are acknowledged in the country’s electricity plan, the 2019 Integrated Resource Plan.

Safcei’s submission problematizes what plans to proceed with these large, costly capital projects would imply for the public purse and for a more sustainable energy future. Our position is that the pandemic should not reverse sustainable development and just transition objectives, but can be an opportunity to bring about an energy mix that is less coal intensive and less nuclear dependent.

ESKOM AS AN INCREASING DRAIN ON PUBLIC FINANCES

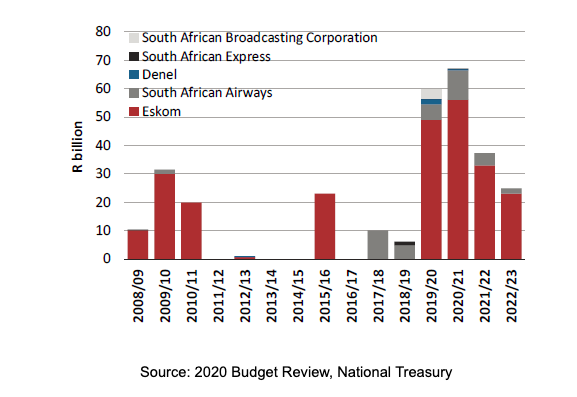

The role of Eskom is significant in terms of the number and the extent of SOE bailouts required. These bailouts are resulting in money that could have been spent on education, health or other areas of spending being diverted.

Figure 1: Financial support provided for State Owned Companies

Treasury noted in the Budget Prelims that "electricity shortages have put the economy under great strain, and demands from Eskom and other financially distressed state-owned companies drain public resources". In February 2020, when the budget speech was delivered, the Minister of Finance announced that an additional R60.1bn was set aside for Eskom and SAA over the next three years. This new allocation was on top of prior allocations, taking the total financial support for Eskom from 2020/21 to 2022/23 to R112-billion. In the same budget, expenditure cuts of R260bn over the next three years were announced. The money that was allocated to Eskom and SAA came from what was cut from government departments. Here are just two examples of how the bailouts took away from other spending. In the February 2020 budget, R4 billion was cut from health funding and it was announced that the National Health Insurance would be phased in slower, as original cost estimates were no longer affordable. This cut came at a juncture when Covid-19 was already affecting other countries placing obvious strain on public health facilities. In the same budget, R1.9 billion was cut from the Education Infrastructure Grant, which came at the same time as there have been repeated incidents at schools with dangerous pit latrines and poorly maintained facilities where children are being taught in unsafe and often overcrowded classrooms.

The driving factor behind the bailouts is contingent liabilities realising. A contingent liability is an obligation (or liability) that may come to pass in the future if some uncertain event occurs. It may or may not occur, but provision is made in case it does need to be paid for. For example, when Treasury guarantees a loan for a State Owned Entity, if the State Owned Entity is not able to pay it back when the loan repayments are due, then Treasury must step in using public finances to repay the loan, because it guaranteed that it would do so. Eskom has taken loans of over R400bn. The value of approved guarantees that Treasury had provided to State Owned Entities by February 2020 was R484.4bn. Of this, the R350bn guarantee to Eskom is by far the greatest guarantee provided. Eskom constitutes the largest exposure to the fiscus.

SOE bailouts are a source of frustration to citizens who through their tax contributions and rising electricity tariffs are footing the bill for looting, state capture and poor management at State Owned Entities. Rising tariffs and taxes add to the rising costs of living for South Africans. There is a prevalent sentiment that the bailouts should not be provided, however the reality is that if a State Owned Entity defaults on the repayment, the lender will come to the National Treasury with the request that the guarantee be honoured. This leaves little choice but to make the bailout. Treasury has provided the bailouts contingent on certain conditions such as improved financial management by State Owned Entities being met, but there are repeated instances in which SOEs have simply ignored the conditions they agreed to before yet another bailout was given.

THE FINANCIAL LINK BETWEEN HOUSEHOLDS, BUSINESSES, MUNICIPALITIES AND ESKOM

Financial challenges at Eskom, municipalities, businesses and at a household level are interlinked with each other. Municipalities onsell electricity from Eskom to businesses and households in their municipal jurisdiction. Municipalities add a markup. They perform a role of maintaining electrical infrastructure assets, but the revenue from electricity sales is not ringfenced for this purpose and exceeds what they spend on maintaining substations. Municipalities also use this revenue to cover the various services that they provide to citizens and businesses. This adds to the cost of electricity. Eskom has begun to push back against the culture of non-payment in South Africa. Non-payment arises due to a range of reasons. To a large extent, non-payment by households is because they have too little income and are heavily indebted due to being affected by the high levels of unemployment in South Africa. Cashflow issues and a high cost of doing business are aspects of what drive non-payment by businesses. There is also non-compliance by those who can afford to pay. Regardless of the reasons for non-payment, when households or businesses do not pay their municipal bills, this affects municipalities, who in turn are in arrears with Eskom. Examining municipalities financial reports and Auditor General reports reveals the extent of poor financial management at a large number of municipalities. This extract from the Auditor General’s Municipal Financial Management report 2017/18 illustrates the interconnected woes of Eskom, local government, businesses and citizens:

The financial woes of local government weighed heavily on municipal creditors. In total, 87% of the municipalities exceeded the 30-day payment period to their creditors – the average payment period was 174 days. The late or non-payment of valid invoices is likely to have a negative impact on the sustainability of small businesses by creating undue cash-flow constraints, ultimately negatively affecting service delivery and employment. Additionally, 39% of the municipalities had more current liabilities than current assets, which means that they will not be able to pay their creditors as these payments fall due. The impact of this inability to pay creditors was most evident in the huge sums owed for the provision of bulk electricity and water. Eskom was owed R18,2 billion (R9,12 billion in arrears by year-end, including R7,5 billion that had been outstanding for more than 120 days) and implemented power cuts at some non-paying municipalities. At the same time, the water boards were owed R9,05 billion, with R5,9 billion in arrears – of which R4,4 billion had been outstanding for more than 120 days. (The amounts for Eskom and water boards were from the municipalities’ financial statements and might be misstated for some of the municipalities that failed to produce credible financial statements.) Some of the reasons behind the inability to pay creditors may stem from weak internal controls in revenue billing and collection. Customers, organs of state, households and businesses owed municipalities an estimated R17,5 billion for electricity and R37,3 billion for water by year-end (source: National Treasury database).

Electricity, water, transport and telecommunications infrastructure are key economic enablers. When this infrastructure is not maintained or does not adequately meet the needs of the country, it stifles business activities and in turn affects job creation. It is therefore critical that South Africa does traverse how to solve its challenges in providing economic infrastructure, including sufficient electricity. Of all these challenges South Africa is faced with, balancing the demand and supply of electricity is the challenge which potentially has the greatest implications on a cost level and for the sovereignty of the country.

ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON SOUTH AFRICA

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa undertook a study into the economic effects of COVID-19 on Africa and expects that growth in Africa will drop from 3.2% to 1.8% and employment will decline by 48%. From 2018 to 2020, South Africa’s average growth was 1.8%. The IMF forecasts that South Africa will experience negative growth in 2020 of 5.8% and the South African Reserve Bank forecasts negative growth of 6.1%. From 2021, both expect a rebound with the South Africa Reserve Bank forecasting 2.2% and the IMF 4%. However, given the prior sluggish growth rates hovering around 1.8% and the prospect of a global recession, these forecasts may be vastly overstated. In this regard, National Treasury notes that “the extent and duration of this downturn is uncertain: economic models are not well-suited to assess a global pandemic, and conditions are changing rapidly. As a result, all forecasts are highly uncertain and subject to change.” In recent years, revenue forecasts have repeatedly been overstated. On 5 May 2020, the South African Revenue Service (SARS) commissioner made a presentation to Parliament. SARS anticipates that the South African economy will contract by between 5.4% and 16%.

At the beginning of March, just prior to lockdown, South Africa had entered into a technical recession. In the immediate days following the announcement of the lockdown in South Africa, there were increased retrenchments as businesses began to take strain or preemptively reduce cashflow requirements. With only essential services operating, businesses are not able to continue their normal day to day operations, except to the extent to which their employees can work from home. Many small businesses and even several large businesses will be faced with insolvency. Contract workers, seasonal workers and other forms of precariously employed individuals are particularly vulnerable to the restrictions that have been put in place to slow the spread of the virus.

While the government has announced a R500 billion fiscal stimulus (around 10 percent of GDP), the stimulus will not completely ameliorate the consequences of the pandemic, nevermind stimulating growth. It is widely known that South Africa has long been faced with the triple challenges of unemployment, inequality and poverty. To add to South Africa’s challenges, Moody’s downgraded South Africa’s sovereign rating to sub-investment grade (junk status). This was announced just days after lockdown commenced. Standard and Poors followed suit at the end of April, with a ratings decision that downgraded South Africa further into junk status. While somewhat inevitable even if the Covid-19 pandemic did not impact South Africa, the downgrades will increase the cost of borrowing. Debt servicing costs were already South Africa’s fastest growing budget expenditure item.

Fiscal policy entails decisions about government’s spending levels and taxation measures to influence the economy. To balance the budget, spending requirements must be provided for. If tax revenue falls short and is not enough to cover the spending requirements, a budget deficit arises and this needs to be addressed by borrowing the money or by reducing spending. When announcing the downgrade, Standard and Poors noted that it expects South Africa’s fiscal deficit to increase to 13.3% of GDP in 2020, resulting in net debt levels climbing to over 75% of GDP by the end of 2020.

In April 2020, when SARS Commissioner, Edward Kieswetter announced the tax revenue figures, net tax revenue was R1 356 billion. Although the amount was R68.2 billion (or 5.3%) more than in the 2018/19 financial year, it still missed the R1 422 billion revenue target that was set in last year’s February budget by R66 billion and also missed the adjusted target of R1 359 billion budgeted in February this year. The 2019/2020 financial year was largely not subject to the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, so these results are only somewhat of an indication of what lies ahead. The result of the revenue outcome is that it implies a budget deficit and spending requirements have not decreased. With the R500bn fiscal stimulus being announced, spending requirements for 2020/21 have increased.

It is expected that the funding for the R500bn fiscal stimulus will come from R200bn credit guarantee scheme, R130bn from reprioritisation of the existing budget, R95bn borrowings from multilateral finance institutions and development banks (International Monetary Fund, World Bank and BRICS bank), R60bn from social security funds and R15bn from Department of Social Development budget. In order to reprioritize within the budget to deal with the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, National Treasury will table a special adjusted budget earlier than October, which is when the adjusted budget is usually tabled. An adjusted budget is tabled each year midway through the year. The purpose of the adjustments process is to “make permissible revisions to the budget, in response to changes that have affected planned government spending for that year”. It is not yet known what areas of spending will be shifted from to find the R130bn. In recent years, there have been spending cuts which have affected departments across the board. The cuts have arisen due to budget deficits and the deficits in turn have arisen due to missed tax revenue targets and needing to find money for bailouts to State Owned Entities.

On 05 May 2020, SARS Commissioner Edward Kieswetter outlined to Parliament that “the impact of the Covid-19 as well as the Sovereign Credit Ratings downgrades is expected to lead to a potential reduction in revenue collections between 5 to 15% - this translates to a range of R71bn and R214bn (excluding any further deterioration in compliance)”. In the outer years of 2022/23 and 2023/24, South Africa’s budget deficit is therefore likely to increase.

IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON DEMAND FOR ELECTRICITY

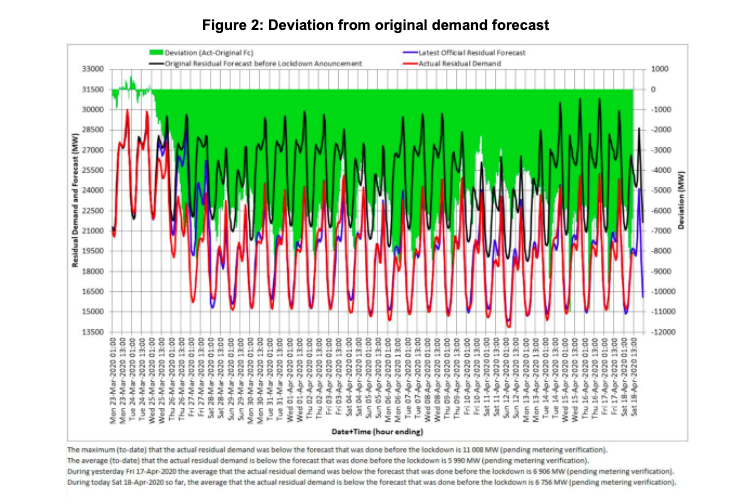

The lock down combined with low economic growth has resulted in a significant drop in electricity demand as a result of a range of businesses activities being suspended for the lock down. The lower demand is expected to persist even after lock down has ended, as businesses start operating again and both SA and global economic activity levels gradually recover. The 900MW currently being contributed by the single reactor operating at Koeberg is significantly less than the 7,500MW - 9,000MW drop in demand reported by Eskom on 2 April 2020 in a press release.

The figure below illustrates how the demand has dropped during lockdown.

Source: Eskom

After the lockdown, the reduction in peak daily demand is expected to be at least 9000 MW. This is close to a third of the average pre-lockdown daily demand of 28,000 MW.

COVID-19 AND A JUST ENERGY TRANSITION

One of the implications of the Coronavirus pandemic is that the United Nations took the decision to postpone the Cop26 climate talks. Cop is a key event in the sustainable development landscape and the agreements emerging from Cop talks are intended to ensure that emissions of greenhouse gases are cut to manage rising temperatures caused by global warming. When announcing the postponement, Patricia Espinosa, head of UN Climate Change provided a reminder that “Covid-19 is the most urgent threat facing humanity today, but we cannot forget that climate change is the biggest threat facing humanity over the long term.” The postponement of Cop26 and the withdrawal of the US in 2017 from the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change mitigation are setbacks at a global level for the just energy transition.

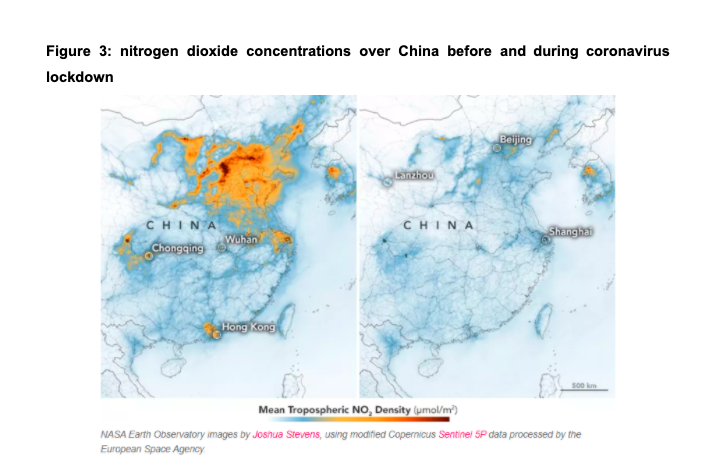

A perhaps unexpected positive impact that lockdown has had is on air pollution levels. The maps in figure 3 below show data collected from NASA and European Space Agency satellites which indicates how nitrogen dioxide, which is released by burning fuel, has dissipated since the outbreak.

In 2018, Greenpeace released a report which highlighted where the world’s largest nitrogen dioxide (NO²) air pollution hotpots are. According to the Greenpeace study which relied on satellite data, Mpumalanga in South Africa has the world’s largest NO² hotspot. Greenpeace attributed this to emissions from the cluster of twelve Eskom coal-fired power plants in Mpumalanga.

In terms of its intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs), SA is aiming to peak Greenhouse Gas emissions between 2020 and 2025, and thereafter plateau them for a decade before reducing. While the Covid-19 pandemic presents an opportunity in South Africa to make policy choices which support to move the country towards less fossil fuel dependence, South African officials are moving in the opposite direction. Minister of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries Barbara Creecy has gazetted sulphur dioxide minimum emission standards that are twice as weak as the previous standards. This is despite the Life After Coal Campaign presenting research to the minister and the department which indicates that 3 300 premature deaths would be caused by altering the emissions standards to support Eskom’s power stations by allowing emissions levels that are about 28 times weaker than China’s emissions standards. The Life After Coal Campaign’s research highlights that these emissions standards will increase the risk of respiratory infections, strokes, and diabetes, which, are not desired health outcomes and even less so during the global COVID-19 pandemic.

The decision comes after environmental rights groups, Ground Work and Vukani, represented by the Centre for Environmental Rights (CER), launched an application to the high court of Pretoria in mid 2019 over the violation of the Constitutional right to clean air. The respondents in the court case are the Minister of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries, the Mpumalanga and Gauteng MECs, the national air quality officer and President Cyril Ramaphosa. The case is being called the deadly air case. The central issue before the courts is the public health hazard caused by the high levels of air pollution in the Highveld Priority Area and whether this constitutes a violation of people’s constitutional rights.

At the same time as the emissions standards were being lowered, Eskom issued notices to

operational wind farms indicating that they would periodically be required to curtail their supply to the grid during the national lockdown and that this was in line with the force majeure (act of God) clause in their contracts with Eskom. This led to the wind independent power producers (IPP) industry needing to seek legal counsel to determine whether the Covid-19 pandemic constitutes a force majeure.

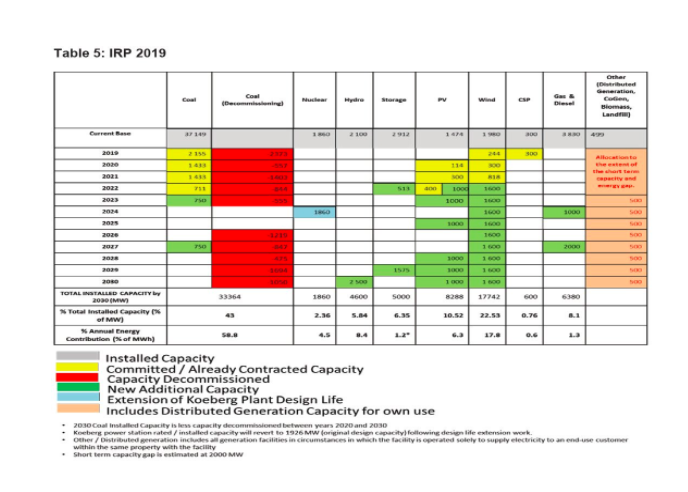

The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) tracks how countries are progressing when it comes to achieving the climate targets they have agreed to under the Paris Agreement. In assessing South Africa’s climate governance, Climate Action Tracker notes in its Sectoral assessment on electricity and heating that “political commitment in the South African electricity and heating sector is poor, as the head of the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) has shown no commitment to ambitious mitigation, climate change focal points are not at a suitably-influential hierarchal level, and neither the Department nor the sector prioritises climate mitigation.” With regards to policy, the CAT assessment is that “South Africa’s electricity and heating sector’s policy processes could be improved. Although monitoring and reporting processes perform well, there are missing concrete steps to tackle long term targets in the largest emitting sector. The 2018 IRP, which has not been formally adopted, includes a 2050 decarbonisation target that has been adopted. However, the 2050 target has been labelled as highly uncertain, with need for additional analysis. The target is also not Paris compatible as coal is still planned to continue to provide 20% of generation capacity in 2050.” This assessment was prior to the adoption of the 2019 Integrated Resource Plan, however in that plan, 1500MW of new coal-powered generating capacity is being planned before 2030. While there is decommissioning of coal powered plants on the cards, coal will be contributing 58.8% of South Africa’s annual energy with a total installed capacity of 33364MW. This can be seen in the figure below.

SOUTH AFRICA’S INTEGRATED RESOURCE PLAN

The Integrated Resource Plan is South Africa’s national electricity plan and is intended to provide a blueprint for the expansion of electricity supply over a specific period of time. Not all countries use an Integrated Resource Planning approach. The use of Integrated Resource Planning came into practice in the context that in the 1970s and 1980s in the United States, financial crises had arisen out of investments that were made in expensive power plants, particularly nuclear power plants that resulted in massive cost overruns. D’sa characterises IRP as “an approach through which the estimated requirement for electricity services during the planning period is met with a least-cost combination of supply and end-use efficiency measures, while incorporating concerns such as equity, environmental protection, reliability and other country-specific goals”. Essentially, an IRP balances supply and demand for electricity following a least-cost approach. In countries where the state manages electricity provision and there are no competitors driving down the cost of electricity, Integrated Resource Planning can improve cost-efficiency of investments, broaden the diversity of the energy mix, improve the reliability of supply and reduce financial risk.

Demand for electricity must constantly be balanced with adequate supply. It is therefore necessary to accurately predict the country’s demand requirements and to allow for a reserve margin which guards against loadshedding being necessitated. A key aspect of the IRP approach is demand modelling which forecasts what the demand for electricity will be.

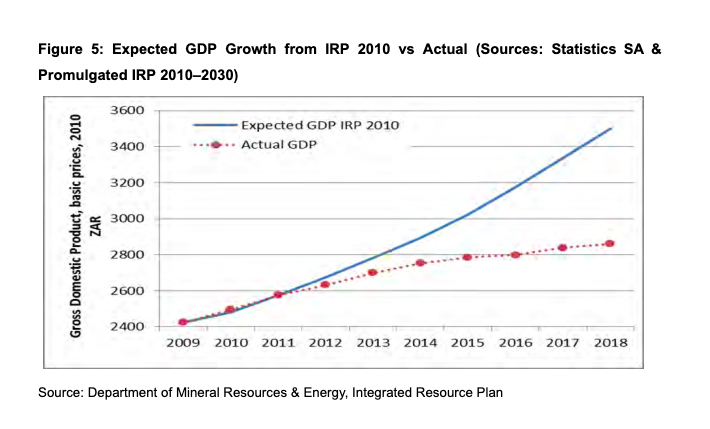

In IRP2019, it is noted that electricity demand did not materialise as projected in the promulgated IRP 2010–2030. The factors that led to lower demand include lower economic growth and improved energy efficiency both by energy intensive users (large businesses) and households.

There is a risk that this will continue to be the trend if the government does not take the economic circumstances brought on by Covid-19 into consideration.

THE ROLE OF NUCLEAR IN SOUTH AFRICA’S ENERGY MIX

The 2019 IRP contains plans to extend the plant life of Koeberg beyond 2024, which is when Koeberg was expected to reach the end of its life. It outlines that Koeberg supplies 1800 MW and that Eskom has commenced preparations to extend its life by 20 years to 2044. These are subject to the necessary regulatory approvals. Once the regulatory approvals are received, the IRP envisions that the plant life extension process will increase the capacity to its original design capacity of 1926MW. The Business Case to extend Koeberg’s plant life was completed in 2010.

While the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy intends to get the procurement process for new nuclear underway, what the IRP says is:

Post 2030, the expected decommissioning of 24 100 MW of coal fired power plants supports the need for additional capacity from clean energy technologies including nuclear. Taking into account the existing human resource capacity, skills, technology and the economic potential that nuclear holds, consideration must be given to preparatory work commencing on the development of a clear road map for a future expansion programme. This IRP proposes that the nuclear power programme must be implemented at an affordable pace and modular scale (as opposed to a fleet approach) and taking into account technological developments in the nuclear space.

In other words, only preparatory work will be done, not immediate procurement and new nuclear is not included in the IRP before 2030. In the IRP, decision 8 is “to commence preparations for a nuclear build programme to the extent of 2 500 MW at a pace and scale that the country can afford because it is a no-regret option in the long term.” At the time when the IRP was released, the wrong version was gazetted. The error was rectified, however it seems that in announcing an intention to proceed with procuring the 2500MW, the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy is adhering to the incorrect version, which said: "immediately commence the nuclear build programme to the extent of 2 500MW because it is a no-regret option in the long term and in case the Inga project does not materialise."

The Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy has now said that both new nuclear and the Grand Inga are proceeding. It should be noted that the IRP refers to a modular scale for the new nuclear build. The country’s prior Pebble Bed Modular Reactor project was pulled after almost a decade and with a price tag of R10bn it had failed to produce any commercially viable electricity generating capacity. The cost assumptions utilized in the IRP for nuclear are based on a DMRE-commissioned study which was conducted by Ingerop. The costings for a state-funded nuclear procurement programme versus small modular nukes could have quite different cost implications, especially if the small modular units are funded by private corporations or foreign State Owned Entities (and subject to High Level Radioactive Waste storage and disposal, decommissioning etc.). It is therefore key that clarity is established about the costs for small modular nuclear reactors.

CONCLUSION

SAFCEI would like to see the South African government making the effort to ensure meaningful public participation that guarantees citizens the opportunity to provide input into the decisions that affect them. SAFCEI and a number of civil society actors want the government to review its decision to extend the life of the Koeberg Nuclear Power Station in the Western Cape and re-look at a decommissioning process as a more viable and cost-effective alternative. Eskom must stop spending money on Koeberg, and invest in affordable, clean and safe electricity generation sources.

Find PDF version with all references and hyperlinks here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ocdNc1lT8CrMmgRrIqO5JxEZpVYUQ_ab/view?usp=sharing

Image Source: SAFCEI[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column] [/et_pb_row] [/et_pb_section]

Who we are

SAFCEI (Southern African Faith Communities’ Environment Institute) is a multi-faith organisation committed to supporting faith leaders and their communities in Southern Africa to increase awareness, understanding and action on eco-justice, sustainable living and climate change.

Featured Articles

-

South Africa: Who Ends Up Paying If DMRE Cooks the Price of Nuclear Power?

-

South Africa’s nuclear energy expansion plans continue to draw criticism, environmental NGOs chew over legal challenge

-

Earthlife Africa and SAFCEI respond to latest unsettling nuclear news regarding the ministerial determination

-

Open Wing Alliance Africa (Virtual) Summit 2023

-

The Green Connection and SAFCEI respond to energy minister's divisive and deflecting comments

-

Job Vacancy: FLEAT Coordinator